-

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Treating Graves’ disease

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: Which usually is the better option for Graves’ disease treatment for someone in their 20s: radioactive iodine treatment or surgical removal of the thyroid?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: Which usually is the better option for Graves’ disease treatment for someone in their 20s: radioactive iodine treatment or surgical removal of the thyroid?

ANSWER: Both options you mention can treat Graves’ disease effectively. But they also permanently eliminate your body’s ability to produce thyroid hormones, so you need to take daily thyroid hormone therapy afterward. Anti-thyroid medication often is recommended before those two therapies because it preserves thyroid function. You should discuss all three options with your health care provider before you move forward.

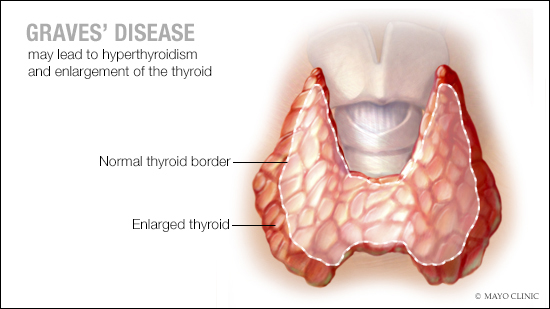

In people with Graves’ disease, the immune system produces an antibody that affects cells in the thyroid gland — a gland in the neck that produces hormones. As a result, the thyroid gland makes too many thyroid hormones. That condition is known as hyperthyroidism.

Hyperthyroidism triggered by Graves’ disease can lead to various symptoms, including unintentional weight loss, rapid or irregular heartbeat, anxiety and irritability, tremors in the hands and fingers, enlargement of the thyroid, and heat sensitivity. In about 20 percent of cases, the disease causes inflammation behind the eyes — a condition known as Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Rarely, people with the disease may develop Graves’ dermopathy — an inflammation of skin on the feet and lower legs.

There’s no treatment available for the root cause of Graves’ disease, which is an autoimmune process. Because of that, treatment focuses on controlling the overactive thyroid. The mainstays of treatment for Graves’ disease, as recommended by the American Thyroid Association, include anti-thyroid medication, radioactive iodine therapy and surgery to remove the thyroid. The one that’s best for you depends on your symptoms, the severity of the disease, your overall medical condition and your preferences.

Anti-thyroid medication often is recommended as the first step in treatment. That’s because it’s the only option that holds the possibility to put the disease into remission while preserving normal thyroid function. The medication that’s usually prescribed is methimazole. It works by making it harder for the body to produce thyroid hormone.

In approximately 40 to 50 percent of cases, anti-thyroid medication leads to remission of Graves’ disease after the medication is taken daily for 12 to 18 months. If testing shows thyroid activity has returned to normal levels after that, the medication can be discontinued. If thyroid activity is lower, but not down to a level considered normal, anti-thyroid medication can be continued safely — usually in a low dose for a longer period of time.

Even if the disease goes into remission after anti-thyroid treatment, it can come back. Follow-up appointments to check thyroid activity usually are scheduled once every six months for the first two years after the disease goes into remission. After that, checkups are scheduled once a year.

There are some drawbacks to anti-thyroid therapy, and it’s not right for everyone. Because it can lead to side effects, people who take an anti-thyroid medication need regular follow-up appointments to monitor their condition closely. Certain anti-thyroid medications, such as methimazole, are not recommended for women who are thinking about becoming pregnant or are at the first trimester of pregnancy.

If you and your health care provider decide that anti-thyroid medication is not appropriate, then radioactive iodine therapy or surgery are the likely alternatives. With the first option, you take radioiodine by mouth. The thyroid needs iodine to make hormones, so the radioiodine goes into the thyroid, and the radioactivity destroys the overactive thyroid cells. Symptoms lessen gradually, usually over several weeks to several months. Surgery involves removing all or part of the thyroid gland.

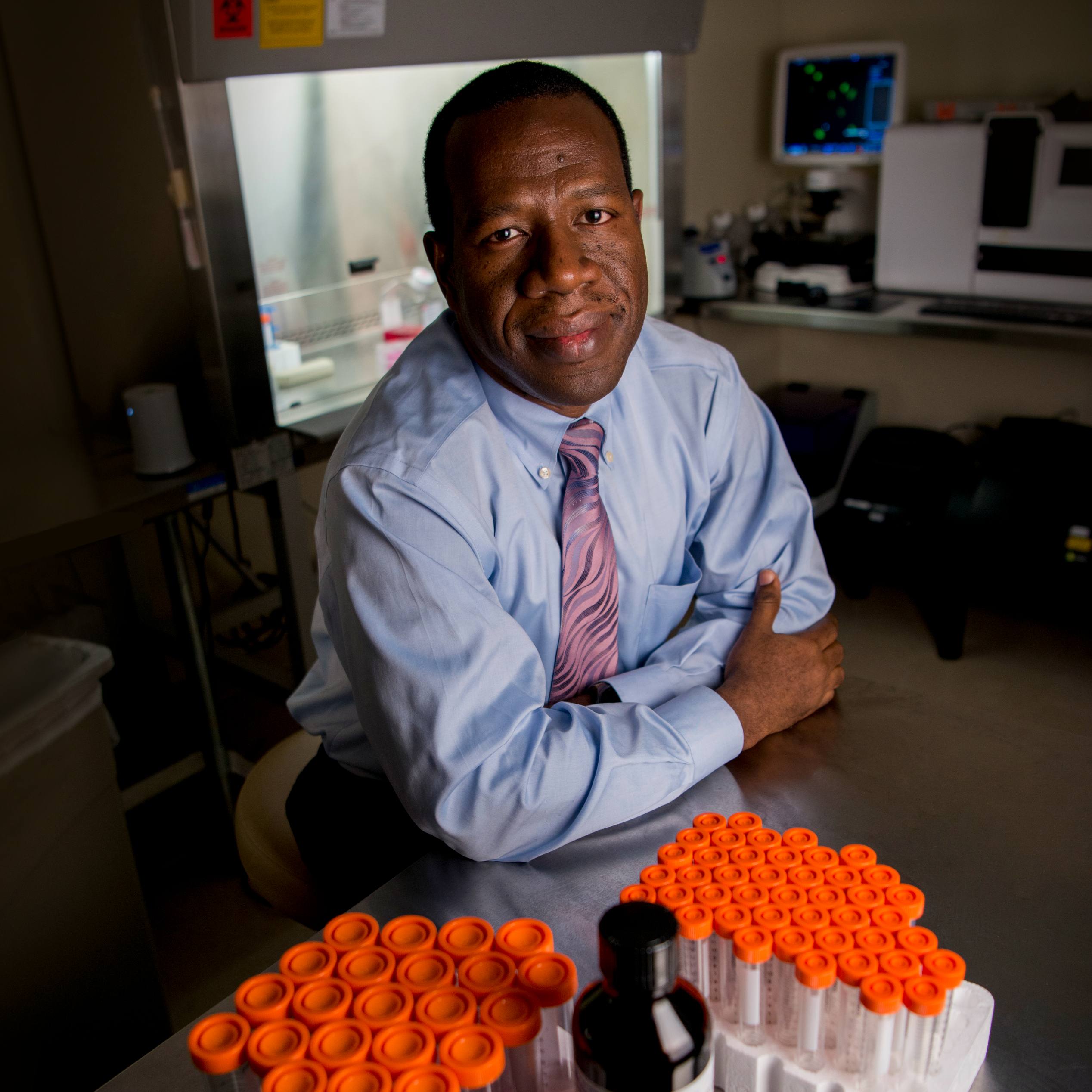

After both radioactive iodine therapy and surgery, you likely will need to take daily hormone replacement therapy for the rest of your life to supply your body with the hormones your thyroid no longer can make. — Dr. Vahab Fatourechi, Endocrinology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota